The #MeToo and #Time’sUp movements have recently made it clear that sexual harassment is a serious and pervasive problem in many workplaces. Third-party workplace sexual harassment is an ongoing issue— particularly for women working in feminized and service- or care-oriented occupations who, because of the devalued social status of their jobs, are often subject to sexual harassment by their clients and customers. While women have been expected to shrug off these experiences as “part of the job,” research demonstrates that there are significant short- and long-term negative consequences for employees including anxiety, depression, fear, and risk of physical harm.[1] Our research project shines a spotlight on libraries as an overlooked site of sexual harassment directed by library patrons towards staff—what we call patron-perpetrated sexual harassment (PPSH). Sexual harassment of library workers is often perpetrated by the very people that library workers endeavour to support.

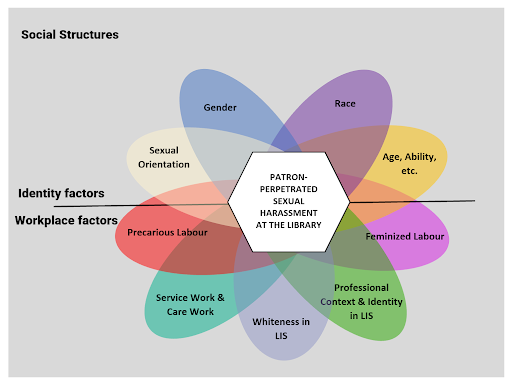

The complex social locations in which library work is situated, along with values embedded within this work (e.g. customer service, commitment to universal access), result in working environments and power dynamics that allow PPSH to flourish—all within broader social structures of dominance including patriarchy, white supremacy, settler colonialism, and neoliberalism. Experiences of PPSH are further complicated by the interconnected and layered aspects of individuals’ own identities such as race, age, and gender.

Intersecting factors that contribute to sexual harassment in libraries

Graphic is slightly revised and taken from Allard, D., Lieu, A. & Oliphant, T. (2020). Reading between the lines: An environmental scan of writing about third-party sexual harassment in the LIS literature and beyond. Library Quarterly, 90(4).

Although libraries are required to have personnel and health and safety policies in place to protect their employees, many of these policies do not explicitly address sexual harassment. Additionally, library workers may receive little to no training about how to deal with sexual harassment by patrons, what resources are available to assist them to address and report this issue, or how to protect and care for themselves during or after experiences of patron-perpetrated sexual harassment. Despite growing calls from those working in libraries very little research has been done on this topic.

Library work has traditionally been, and continues to be, dominated by white women—81% of library workers identify as female and 87% identify as white.[2] This has many implications for how library work is perceived and embodied, including the pervasiveness of PPSH and the (in)ability to combat it. We recognize that workers who have marginalized identities – such as BIPOC, queer, and/or disabled folks – experience PPSH in ways that are complex and nuanced. We also acknowledge that gender and race inform and affect all aspects of society. Our work is situated broadly within intersectional feminist and anti-racist frameworks that make visible and interrogate the feminized and racialized nature of librarianship and the attendant implications of this for all persons working in libraries. Using and believing the many and varied experiences of library workers to frame theory and action, our intersectional feminist approach is generated from library workers’ lived experiences and epistemological perspectives.

Our research initiates conversation among LIS students, educators, library workers, administrators, and patrons to raise awareness about the pervasiveness of patron-perpetrated sexual harassment in libraries and to destigmatize and combat what we argue is a harmful yet “everyday” form of gender-based violence.

This research project has 4 phases:

Phase 1 – Environmental scan: We conducted an environmental scan of the extant literature to develop a typology of the facets of third-party sexual harassment across related disciplines (women’s and gender studies, healthcare, retail and hospitality studies, and organizational studies.) Findings from this environmental scan are published here. See also the graphic included above. More information about our survey findings can be found here.

Phase 2 – Library worker survey: To gather and analyze the experiences of patron-perpetrated sexual harassment of library workers, we conducted a national online survey of library workers’ experiences of PPSH. More information about our survey findings can be found here.

Phase 3 – PPSH policy review and analysis: We will identify and analyze best practices with respect to harassment-related public library policies, reporting procedures, and both library employee and patron codes of conduct. To contribute to this review, please take our Sexual Harassment in Libraries Policies and Procedures Survey here.

Phase 4 – Dissemination of results: We will disseminate our findings in a variety of forms (e.g. book, website, workshops. Our results will contribute to LIS and feminist consciousness raising, scholarship, and practice that opposes and undermines gendered power structures that endanger library workers and make them vulnerable to gender-based violence.

Our research has been funded by the Faculty of Education, University of Alberta and by Killam Operating Grant, University of Alberta, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

____________________________________________________________

[1] Alberta Human Rights Commission. (2017). Sexual Harassment. Retrieved from https://www.albertahumanrights.ab.ca/publications/bulletins_sheets_booklets/sheets/hr_and_employment/Pages/sexual_harassment.aspx; Chan, D. K. S., Lam, C. B., Chow, S. Y. and Cheung, S. F. (2008). Examining the job-related, psychological, and physical outcomes of workplace sexual harassment: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(4): 362–376. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00451; Willness, C. R., Steel, P., & Lee, K. (2007). Hostile environment indeed: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Personnel Psychology, 60(1), 127–162.

[2] American Library Association. (2017). 2017 ALA Demographic Study. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/tools/sites/ala.org.tools/files/content/Draft%20of%20Member%20Demographics%20Survey%2001-11-2017.pdf